Optimizing the Clinical Encounter: The Science of Listening

Optimizing the Clinical Encounter: The Science of Listening

It is the province of knowledge to speak, and it is the privilege of wisdom to listen. - Oliver Wendell Holmes

It seems like everyone's talking about health disinformation, AI, large language models, and other digital health tools. With all these new tools and emerging issues, it's a good time to take a step back and explore the overarching role of communication and the physician-patient relationship.

The average outpatient clinician will conduct 100,000 medical interviews over the course of their career, making it easily the most common medical procedure. Almost every medical student knows two basic facts: that doctors interrupt patients within about 15 seconds of opening their mouths, and William Osler's aphorism, “Listen to the patient; he is telling you the diagnosis.” When we compare the time and energy we put into teaching and studying medical procedures like thoracentesis and cardiac auscultation, it’s striking how little emphasis we have placed on communication. And when we do consider communication, our training focuses on what we should say, not how we should listen.

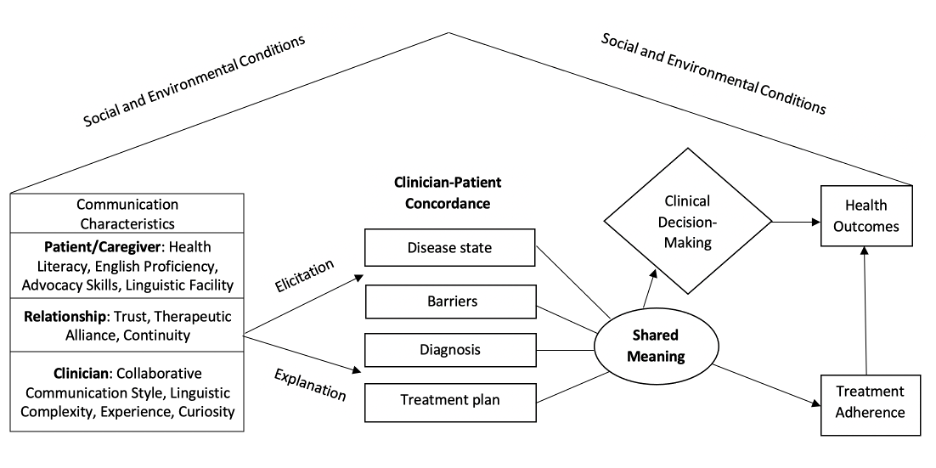

The following is a roadmap for listening in the context of outpatient clinical care. The patient brings to the visit a variety of social and environmental conditions, and the clinician has several characteristics that they bring as well. The patient and caregiver will generally have different levels of health literacy, English proficiency, linguistic facility, and advocacy skills, including the ability to describe their own narrative. The clinician brings her own attributes, including curiosity and the ability to listen. There are also attributes of the relationship that impact the effectiveness of the clinical encounter, including the degree of trust and continuity of care that exists.

Communication researchers Mary Catherine Beach and Ronald Epstein have found that there are three types of listening:

1. Task-focused listening

2. Contextual listening

3. Relational listening

Listening with a diagnostic ear is a form of task-focused listening, and requires pattern recognition, judgment, categorization, confronting one's confirmation bias, and facilitating clinical reasoning. In contrast, contextual listening takes a broader view of the patient's life, recognizing that the response to illnesses is conditioned by family, social support, finances, education, literacy, resources, and structures of power. Finally, relational listening involves attending to, clarifying, and validating patients' concerns, values, beliefs, and emotions, and confirming shared understanding. Only by connecting these three types of listening can we align clinicians' efforts with what matters most to patients and ensure that patients are accurately understood and better prepared for treatment.

In most communication research, much of the focus has been on doctors explaining things well, and very little has been focused on the degree to which we elicit, listen, and respond to patients appropriately. What do we need to elicit from the patient, in addition to their overall story? At a most fundamental level, we're interested in the state of their disease.

If the patient has heart failure, are they in class II or class III? If they have diabetes, is it poorly or well controlled? If they have depression, how severe is it? What are the barriers to the self-management of the patient’s chronic illness? Few patients come in saying “actually, I'm not taking my meds because I can't afford them” or “I'm not doing the physical activity we talked about because I'm so depressed.” We need to be active listeners, seeking out barriers to self-management, and creating shared meaning between clinician and patient.

Our research group conducted a study in a cardiac clinic to assess patient-physician concordance on New York Heart Association classification. After the initial visit, we asked physicians to determine the class of heart failure (we had already determined the class in a pre-visit with the patient.) Physicians misestimated the class by greater or equal to one level in half of the visits, including under-classifying 75% of patients with Class IV heart failure.

Appreciating the importance of a shared subjective understanding led us to conduct a randomized trial on mirroring patient language. In this study, visits involved complaints related to sexual or excretory functions of anatomy (for example, “I'm itchy down there”). Physicians who matched the vocabulary used by their patients scored better on measures of rapport, patient distress, and communication comfort, and achieved greater adherence to the recommended treatment. In other words, matching the patient's language was associated with better outcomes.

We scaled this research by studying secure messaging at Kaiser Permanente. Our study involved thousands of primary care physicians, tens of thousands of patients, and hundreds of thousands of secure messages. We used natural language processing and machine learning to categorize physicians' language use as either having high or low linguistic complexity, and patients' language use as having either low or high health literacy. Our key findings were that clinicians who listened to how the patient spoke and matched their style experienced fewer communication disparities. Physicians could eliminate disparities in shared understanding by tailoring their language to each patient, thereby achieving shared meaning.

Abraham Verghese and colleagues examined the technical practices to help foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. In a mixed-method study, they identified the top five practices that were deemed to be the most effective and feasible. Four of the five involve active listening:

- Prepare with intention - familiarize yourself with the patient before the visit.

- Listen intently and completely - active listening has been associated with gains in patient rapport and in patients’ understanding of their diagnosis and treatment plan.

- Agree with your patient on what matters most to them, and to you - collaborative agenda setting has been associated with higher patient ratings and reductions in pain and anxiety. Importantly, it only increases the visit time by about one minute.

- Connect with the patient’s story - curiosity about patients’ experiences has been shown to be associated with reductions in racial bias and impressive improvements in health outcomes.

- Explore emotional cues - exploring emotional cues is associated with improved ability for patients to learn new information, higher appointment and treatment adherence, and better health outcomes.

A 2009 study of the treatment of the common cold showed that patients whose physicians explored their emotional cues had a shorter duration of cold symptoms (from 7.0 to 5.9 days). The improvement was mediated by increased interleukin-8 levels, pointing to the possibility that better listening and responding to emotional cues leads to positive changes in our immune response to illness.

Saul Weiner defines contextualized listening as ‘the process of adapting research evidence to the patient life context’, as outlined in the 4C Method. First, you identify a Contextual Flag such as poorly controlled blood pressure. That Flag should prompt a Contextual Probe to identify factors like lack of resources, limited access to care, cultural perspectives or spiritual beliefs, or attitudes towards the health care system that may serve as barriers. These Contextual Factors all influence whether a Contextualized Care Plan will be successfully implemented. In our own heart failure work , we identified significant missed medication (67%) and psychosocial barriers (69%). Weiner and his team recently conducted a study at the VA and found that physicians who received contextualized listening feedback were more likely to probe and contextualize their care plan, resulting in better health outcomes, a 2.5% lower hospitalization rate, and $25M in savings.

Finally, a functional MRI study demonstrated that active listening by clinicians to patients’ descriptions of a traumatic event was associated with a greater sense of satisfaction and rapport with the clinician and a greater willingness to follow the clinician’s recommendations. Active listening was also associated with an emotional reappraisal of the event by the patient, wherein the event was re-perceived in a less negative light. In the fMRI images, the ventral striatum of the thalamus and the right insular cortex lit up. The ventral striatum is part of the limbic system and is known as the ‘critic’ of the pleasure center and reward system. The insular cortex is responsible for emotional reappraisal of memory. In other words, active listening was associated with significant and positive changes in patients’ actual neurophysiologic processing of traumatic events and a greater willingness to follow clinicians’ recommendations.

"Undivided attention is a core tenet of the deep work of doctoring,” writes behavioral health researcher Elizabeth Toll. “It invites the patient to tell their full story and the physician to listen with openness and curiosity without judgment. It allows for solution-shop work, not production-line work."

Solution-shop work moves us away from an industrial model of clinical visits as a series of individual transactions and toward a more human-centered model, with multifaceted solutions emerging from relationships. A deeper appreciation of the importance of listening – combined with new tools including AI – will allow us to engage in the deep work at the heart of our profession and improve patient outcomes.

Dean-David Schillinger, MD

Director, UCSF Health Communications Research Center

Professor and Co-founder, UCSF Action Research Center (ARC) for Health Equity

Author of Telltale Hearts: A Public Health Doctor, His Patients, and the Power of Story