The State of the UCSF Department of Medicine

The Department of Medicine has been my professional home for more than 30 years. Yet it is only in the last eight months, as interim chair, that I have gotten a window into the department’s true scope and magnificence. These months have also given me a deeper appreciation of the challenges the department faces.

Bob Wachter speaking to Department faculty and staff on March 3rd.

In this blog post, and a parallel address (which I gave at Parnassus on March 3rd and will deliver at several of our other sites in the next few months), I’ll describe the current state of the department, highlighting our achievements and struggles. I’ll also briefly touch on a few of the initiatives we’ve undertaken to address the issues.

The achievements are myriad. Across all of its missions, our department (and UCSF in general) is at or near the top of virtually every ranking. In a worldwide ranking of universities, in the category of Clinical Medicine this year we were second in the world, behind Harvard. In its annual ranking of medical schools, US News & World Report placed us 3rd in research and 3rd in primary care, the only school to make the top 5 on both lists. In clinical care, UCSF Medical Center again made the US News "Honor Roll" of top ten hospitals, this year coming in 8th. While all these rankings have their problems, they paint a picture of an organization that is widely admired for its work in clinical care and education.

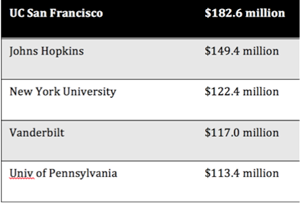

In research, our department is the top recipient of NIH grants of any department in the U.S.; our $182 million in 2015 tops second place Johns Hopkins by more than $30 million. In a very tough funding environment, our NIH funding has continued to climb, as it has from non-NIH sources as well. I’m particularly proud that the research is widely distributed, with substantial contributions coming from SFGH and the VA – in fact, our HIV, ID, and Global Medicine division, based at SFGH, is our largest recipient of NIH funding.

2015 NIH Funding, Departments of Medicine.

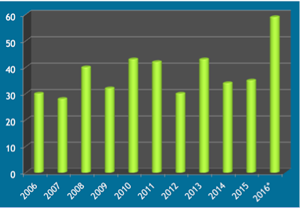

Our department’s educational programs are extraordinary. Our medical student rotation is the most highly ranked in the School of Medicine. On the influential Doximity website, our internal medicine residency ties for third with the Brigham. Remember a decade ago when students were shying away from internal medicine? Things have been improving gradually for the past several years, with an average of 35 members of our graduating class of 150 students applying in medicine over the past few cycles. This year, however, 59 of our students applied to medicine residencies. We must be doing something right!

UCSF Medical Students Applying in IM, 2006-16.

Our philanthropy has also skyrocketed: in 2011, gifts to the Department of Medicine totaled $15 million. Last year, the figure was $40 million. Of course, some of that owes to the wealth of our surrounding community, but donors don’t give to people who are not doing exciting and meaningful work. Ours are.

At our other clinical sites, things are also going well. Let me particularly highlight the buzz at SFGH, with a spectacular new hospital opening in a couple of months, a research building slated for 2019, and the likely implementation of UCSF’s Epic system (APeX) over the next couple of years. The Affordable Care Act has given many previously uninsured patients access to MediCal or insurance through the Exchange, which has provided unprecedented revenues to SFGH. Things are more mixed at the VA, where some new money materialized after the Phoenix waiting list scandal, but has eroded after some major cost overruns associated with some major (non-SF) construction projects. But overall, things are going well there too.

With numbers like these, it should be the best of times. Yet there is a deep unease as well. For the past few years, faculty and staff at our UCSF Health sites have been completing a standardized survey to gauge their engagement, generally felt to be the most meaningful metric for organizations. Engagement seems to be related to pretty much everything: recruitment, retention, performance, likelihood of recommending the organization as a place to work or to receive care.

Last year’s numbers were disquieting. On a scale of 1 to 10, 10 being the highest, on the questions of "a good place to work," there were more "detractors" (scores of 1-6) than "promoters" (scores of 9-10). The ratio of promoters to detractors is known as the Net Promoter Score (NPS), and well-regarded businesses typically have scores in the +30-50 range, although healthcare organizations tend to come in a bit lower. Our scores last year – for clinically active faculty at UCSF Medical Center – were -11.

There were already significant efforts underway to address some of the main issues, particularly in the ambulatory care environment. Last year, after seeing these numbers, we redoubled our efforts – a group led by Diane Sliwka, a faculty member in our department, has been addressing scores of issues, from amenities in the operating room to staffing in the clinics. Notwithstanding these efforts – which have involved major investments – our scores this year went down, to -22. (The scores within DOM are about the same as those from other departments.) This is disheartening, to say the least. But it is what it is, and we need to try to understand it, and address it.

It’s important to point out that there is significant variation across our department. Some divisions have scores in the +20-30 range, which shows that faculty engagement is achievable. But others have scores that are even lower than the mean. If there’s any pattern to the numbers, it appears that divisions that have been split up geographically – with significant numbers of faculty at MZ and Mission Bay as well as Parnassus – tend to have the lower scores. This is also true for divisions whose work is focused in the ambulatory world.

I’ve written previously about burnout so won’t belabor the point. As I look at the numbers, I think they are less about money (though clearly folks are struggling with SF housing prices) and more about Daniel Pink’s famous trilogy: people who are engaged in their work tend to prize autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Our increase in size, our geographic spread, the adoption of the electronic medical record, the uptick in documentation and regulatory requirements, the decrease in face-to-face contact – all of these have come at the cost of autonomy, mastery, and purpose. And community.

On top of that are some massive changes in the health care system, ones that everyone is struggling with nationally. UCSF's health system is far bigger than it once was, a necessity in today’s competitive market, where "scale" is the name of the game. Our new funds flow, a critical element of health system-MD integration, has led to a physician compensation model that seems to prize production (more visits) over all else – at a time when we’re being told that the name of the game is increasingly not production, but value.

And, while our resources are in decent shape today, the future is cloudier. In the world of academic health systems, there are only two things we do that produce surpluses: clinical medicine and philanthropy. (Yes, we do get dollars from the state, but after decades of cuts, this amounts to a small fraction of our resources.) There are several other things we do that run at losses and need to be subsidized: research (even well-funded researchers are rarely self-sufficient), education (of course), community work, and some non-procedural clinical services (primary care, hospital medicine, infectious diseases, to name a few). This, of course, has nothing to do with the true value of the work; it is simply an artifact of the payment system. Yet it means that we are utterly dependent on clinical revenues to cross-subsidize the rest of our missions.

Unfortunately, our clinical revenues are threatened as never before, by a series of forces that range from the Affordable Care Act to major changes in the insurance market. More patients with MediCal under the ACA translates to more patients at a UCSF Health site. This is probably good for society, but – since MediCal pays far less than the true costs of care – it’s bad for the bottom line. (As I said earlier, it’s been a positive thing at SFGH, where many previously uninsured patients now have a source of payment.) On the commercial insurance side, more patients are choosing less expensive health plans, some of which restrict access to UCSF physicians, under so-called "narrow networks."

These are challenges, to be sure, but they are ones that we can overcome. We’re working hard to do just that. We’re working with the health system to plot and execute a strategy that will allow us to thrive in the new environment. This means that we need to pursue new models of care, place greater emphasis on population health, and improve our patient access and our value (quality divided by cost).

On other fronts, we’re pushing hard for appropriate office space for our faculty and staff, trying to learn the lessons of Mission Hall as we remodel that building and open up other new buildings. We’re also working with the school and health system to create new housing options and choices for childcare. We’ve pumped more than a million dollars into ensuring pay equity for our female faculty members, and a task force, led by Beth Harleman and Rene Salazar, is charting our departmental strategy to improve diversity and inclusion – one that should sync up with the many activities already occurring on campus.

I’m on an exciting task force, led by Provost Dan Lowenstein, that is considering the future of Parnassus and Mt. Zion ("Parnassus/MZ 2025"). Our report will come out in a few months, but I think we’ll have some bold recommendations about how to reinvigorate these campuses, sites that have received insufficient attention and investment as we’ve built out Mission Bay.

I’ve emphasized the plight of clinicians and educators, but our researchers are also suffering under the weight of NIH funding cuts. In the 1990’s and 2000’s, about 35% of NIH grant applications were funded. Today, it’s less than 20%, which makes UCSF researchers’ success all the more impressive. To support our researchers, our department is doing what it can to help, including by trying to improve our infrastructure and creating the iRAPS ("In Residence Associate Professor Support") program. As you may recall, iRAPS will provide $50,000 per year in "hard money" salary support for researchers in the In Residence series who are promoted to associate professor. This program has proven to be tremendously popular, and I believe it’s crucial to our efforts in recruiting and retaining the nation’s top researchers – and allowing UCSF’s research environment to continue to flourish.

The bottom line is that, while these really are extraordinary times for UCSF and our department, they are also a time of enormous growth and change, and with that comes considerable anxiety. We are far from alone – every academic medical center in the U.S. is going through a version of our challenges, and many of the challenges are not limited to academia.

My personal belief is that we will soon enter a golden age in medicine – as the new organizational arrangements and policy/payment initiatives settle out, as we move to a more mature state of digitization, as the promises of precision medicine are achieved, and as we begin to reinvent our work and workflow to maximize the use of our most precious resources: our people. There will be winners and losers – the former will be organizations populated by great people who are well supported and doing meaningful work, in an environment characterized by enthusiasm, collaboration, teamwork, diversity, and innovation.

In other words, we’ll be fine.

Robert Wachter, MD

Interim Chair, Department of Medicine