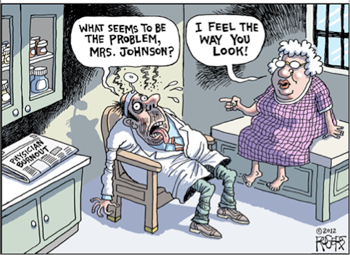

Physician Burnout and the "Quadruple Aim"

Physicians should be a happy lot. We do fulfilling work. We are trusted and admired by society. Our unemployment rate is negligible. We are reasonably well compensated. We have TV shows written about us.

Yet a tide of burnout and angst is sweeping our field, and it is crucial that we address it.

In early 2013, I called Brian Sexton, a Duke psychologist and one of the leading experts on patient safety culture ("no blame," will clinicians report errors, that sort of thing). I had interviewed Sexton seven years earlier for a federal patient safety website I edit, and my 2013 call to him was for another interview in which he’d give us an update on where we were in our efforts to improve safety culture.

But as soon as I raised the topic, he stopped me. He didn’t want to talk about patient safety culture, you see, despite the fact that this had been his life’s work. Instead, he wanted to talk about burnout and resilience.

As Sexton explained it, he is seeing physicians and other clinicians that are so burned out with clinical demands – and so overwhelmed by initiatives to improve safety, quality, teamwork, patient experience, efficiency, and more – that they simply can’t do one more thing. "It’s like Maslow’s hierarchy," he told me: clinicians can’t focus on these higher goals if they themselves are depleted.

We see signs of this burnout all around us. Too many physicians feel that their ability to practice medicine – and to find satisfaction and fulfillment in that practice – has been eroded by everything from overzealous regulations to the entry of the electronic medical record into their exam room. (Our DGIM faculty estimate that they spend three hours each night documenting their day’s work and emptying their electronic in-boxes.) A 2015 Medscape survey found that 50 percent of physicians met criteria for burnout, a 15 percent increase from only two years earlier. Women suffer significantly higher rates of burnout than men.

Why should anyone care about whether physicians are happy? Because our ability to care for patients and improve our systems of care is tightly linked to our joy in practice. In fact, in an important 2014 article, UCSF’s Tom Bodenheimer, together with Christine Sinsky, an internist who now leads the AMA’s initiative on Professional Satisfaction (and who will be giving medical grand rounds at Parnassus this Thursday, October 15th, at noon), argued that we should broaden our goal from achieving the "Triple Aim" (better healthcare, better health, lower costs) to achieving the "Quadruple Aim" (adding clinician satisfaction).

Thankfully, attitudes about physician satisfaction are beginning to change, and this is leading to tangible actions, both locally and nationally. When Diane Sliwka was asked by the UCSF Health System to take a leading role in improving the patient experience, it rapidly became clear that doing so would require addressing the provider experience. So her title morphed – into "Medical Director for Patient and Provider Experience." Jeff Critchfield, the Chief Patient Experience Officer at SFGH, also co-founded a group to help clinicians process their feelings after an adverse event. Across our sites, work is being done to optimize the practice environment, an investment that partly owes to a realization that unhappy clinicians cannot create happy patients. Our earlier hope that systems improvement work could be layered on top of a full-day’s clinical or academic schedule is giving way to a more mature understanding that this work takes skill, time, and emotional bandwidth.

At UCSF, we’re truly lucky to have several other sources of joy and resilience beyond those that come from direct patient care. There is little that is more rejuvenating than teaching a student or mentoring a resident or fellow. Or more gratifying than creating new knowledge that enhances our understanding of how to treat disease. Yet these things also take time, support, and resources. Without them, these missions can become yet another source of frustration and burnout.

What can we do? We will continue to highlight the connection between our professional environment and the outcomes that we want for our patients. We need to partner effectively with our health systems and our colleagues to build the practice environments that translate into both professional satisfaction and enhanced patient outcomes. We must think more creatively about new ways of using technology that actually contribute to, and don’t detract from, these goals. We need to strive for a work environment that recognizes that professional excellence is impossible without diversity, collegiality, and work-life integration.

Clearly, compensation is a piece of this (particularly in face of the Bay Area’s real estate market), but it is not everything. While people need to be fairly compensated for what they do, the work of Daniel Pink and others demonstrates convincingly that intrinsic motivation – "autonomy, mastery, and purpose" is Pink’s holy trinity – is the main ingredient in the recipe for professional fulfillment. If we are going to succeed in all of our missions, we simply must have a vital, happy, and engaged workforce.

Many years ago, when I was still at SFGH, I attended a faculty meeting in which we discussed all the changes coming down the pike: more regulations, more public reporting, lower payments, tighter NIH budgets, electronic health records… the whole House of Horrors. Mel Cheitlin, a wonderful (and senior) SFGH cardiologist, grabbed the microphone, something he didn’t often do at these meetings. I assumed he was going to complain about the profession going to hell in a hand basket.

"You know," he began, "this could be worse." I was stunned, but then he continued.

"I could be younger."

While Mel’s sentiment was, and remains, understandable, I believe we’re on the cusp of a golden age in medicine, one in which we finally create a system that delivers high value care for our patients and allows physicians and other clinicians to practice with enthusiasm. I’m optimistic because the mandate to do the former is growing rapidly, and the evidence that you can’t achieve high value care without joy in practice becomes more compelling every day.

That means that professional satisfaction is no longer a nice-to-have, kumbaya kind of thing. It’s an imperative.

Robert Wachter, MD

Interim Chair, Department of Medicine